social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

Let me tell you about …

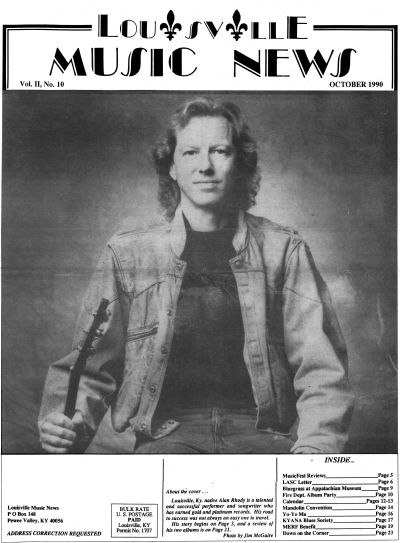

Alan Rhody

Performer and Songriter

By Jean Metcalfe

October is Country Music Month. It seems only fitting, then, that we feature a "hometown boy" who has hit it big in country music.

October 1990 marks Alan Rhody's twentieth year as a performer and songwriter. I have enjoyed Alan's music and followed his career since I first heard him some five or six years ago. I am a Johnny-come-lately to the music of this talented man. He earned my admiration as an outstanding performer and songwriter from the moment I heard him sing "I Love You Anyway Uncle John."

Sitting in the Louisville home of his wife's parents, the personable entertainer lit up a small cigar as he verbally led me along the path he traveled to arrive at this milestone in his career. The way was not without twists, turns and obstacles, but Alan managed to earn several chart hit songs and collect multiple gold and platinum records along the way.

"As far as the business goes, I became a professional musician, in my mind, around 1970," he said. "But what made me get into the business started probably when I was ten years old, which was hearing music on the radio by Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Johnny Cash, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and all those kind of people, the pioneers of what I think of as country blues and rock 'n' roll and rockabilly."

"My older brother Lannie and I were just mesmerized by the radio back then. We'd go out and buy stacks of single records. And I'd go around singing with this stuff all the time but it never entered my mind to go out and try to perform myself."

Alan continued to listen to music all through his high-school years. He had the good fortune to see Roy Orbison, one of his "huge favorites," when Orbison was a "huge, huge hit" at what was then called the Middletown (Ky.) Hop at the elementary school.

"They had some of the best rock 'n' roll shows out there through the Sixties as anybody I can think of in the country. They might have even had chaperones there, for all I know. I didn't notice. I was too much in a trance," he laughed.

Rhody had also seen Bo Diddley, Frankie Ford and James Brown for "like two bucks at a teen dance, when they were doing that kind of school circuit. In those days that was a big market for people who had records out."

"Now," he said, "it has all gone to concerts and night clubs with booze, which is where they have to make their money."

From about the time Alan was in the ninth or tenth grade he knew he wanted to be an artist (a painter). He had a real "given" talent for it, he liked doing it, and his parents encouraged him "a good bit."

When his junior year rolled around he was thinking only of a career in art, and pondering what school he would be attending after high school graduation (from Eastern High School in Middletown). Despite his love of music, Alan had no thoughts of making it his career.

While in his senior year, a friend invited him to a Peter, Paul and Mary concert at Freedom Hall, and the trio made quite an impression on him. In about 1964, Alan and a neighborbood friend (whose older brother brought home sample records that were given to him by the radio station where he worked) put Bob Dylan's "Maggie's Farm" on the record player. "It was the strangest sound that either of us had ever heard. . . . It wasn't bad, it was just strange sounding to us." Alan and his friend were into rock 'n' roll, and "the Beach Boys were real big then." Dylan's music "didn't grab me, it was just like what is that? . . . I didn't know what to make of it." He'd never heard of Dylan.

After high school graduation, Alan attended on a full scholarship and graduated from the three-year program at The Art Center Association School on First Street in Louisville, formerly a part of the Art Department at the University of Louisville. "I was just in hog heaven as far as being an art student goes," Alan said.

When Alan was 19 and in his first year of art school, he joined a rock 'n' roll band. Seems an art school friend, Bill Gdaniec (now of Gdaniec Graphics) was in a band, and "I thought that was great, that I knew somebody in a band," Alan admitted. The friend invited Alan to attend a band practice in the basement of his home, and "I guess by that time (Alan is chuckling now) I sorta wanted to say 'Hmm, I think I'll try singing a song,' you know, more than just singing to myself around the house."

At the band's invitation to sing for them, Alan selected "Bring It On Home to Me." "And I guess . . . singing into a microphone for the first time and all that stuff, you go, 'Man, this is great,' your voice is amplified. I couldn't sing that well, I don't think."

The band members apparently thought he sounded okay, and invited Alan to join the group. He didn't play a musical instrument, so they suggested he buy a harmonica, learn to play it, and he could be in their band. "And that's what I did." Alan chuckled at the recollection.

(I had come to the interview expecting to hear that Alan had been playing a Sears-catalog guitar since he was big enough to hold one in his chubby, baby hands. I knew he played harmonica, but I had supposed that came later, after guitar.)

That first band, "The Kingspades," did mostly Beatles, Rolling Stones and Chuck Berry tunes (with emphasis on the Beatles); they were strictly a cover band. "There weren't too many original bands then," Alan recalled.

"At one point we even had Beatle haircuts, which is something that I'd rather not remember, as far as the way I looked," Alan said with an embarrassed laugh.

"We wore black turtlenecks with red vests and black pants and Beatle boots, when we 'really got it together.'"

Alan's stint with The Kingspades lasted eight or nine months. During that time they got into some battle-of-the-bands contests and came in as high as third, although high school dances were their most frequent gigs.

At about the time Alan left the band, he recalls, he saw Ian and Sylvia on "The Bell Telephone Hour" on television. The duo sang Ian's "Four Strong Winds," and Alan loved it. It was also around that same time that he "bought a Silvertone guitar from a guy down the street in Middletown for about $18" and learned, on three strings, "Don't Take Your Guns to Town," a Johnny Cash song.

"I became a professional musician, in my mind, around 1970."

The guitar "was real bad. You could hardly play it," Alan said. He did not mean "bad" in today's slang sense.

After first canvassing the pawn shops on Market Street in downtown Louisville, Alan bought a classical guitar from Durlauf's, a music store on Fourth Street near Vine Records (where he often shopped), because the nylon strings would be easier on his fingers.

Later on, a friend, Bob Parker (whom Alan credits with getting him more into folk and country and acoustic music), played Bob Dylan, Jimmie Rodgers, and Flatt and Scruggs records and that was "like a milestone to me," Alan said, "because I'd never heard that kind of stuff. When I was growing up in Mississippi and Hopkinsville I heard country music on the radio but it never appealed to me . . . 'cause that was when Elvis hit. . . . Country music to me at that time was just this whiny, cornball stuff."

The mention of Alan growing up in places other than Louisville provided an opportunity for me to inquire about his family, and to elicit other personal information.

Born in Louisville, Alan was the second oldest of the five children of Maurice and Eugeania Raye "Jean" Kohnhorst. Maurice Kohnhorst was a social worker whose various positions required that he re-locate numerous times.

"By the time my family moved back to Middletown, and I was getting ready to go into the eighth grade, I had changed schools six times," Alan recalled. "That'll turn you into a songwriter right there," he added.

Alan is married to the former Kathy Sigler, whom he met while they were attending art school. In 1964-65 before Alan and Kathy met, she was taking night classes at the school and was the first official apprentice at Actors Theatre of Louisville.

Kathy and Alan have three children. Bridgette, 22, attends the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, where she is an English major with a minor in dance and theater. Colin is 21 and lives in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he is studying to be a sculptor. Heidi, 17, is a senior in high school in Nashville, where she is taking art. According to her father, she is doing well at it, and also seems to have the best singing voice of their three children.

When Bob Parker had first played "Girl From the North Country" for Alan, he was really impressed. "I thought, man, where did this come from?" Upon being told that it was a Bob Dylan song, Alan wondered, "Who is Bob Dylan?"

Along about that same time a friend, Jim Guthrie, was playing guitar and singing songs at lunch time at art school. Alan skillfully imitated his friend: "He (Guthrie) would say, 'Yeah, that was Bob Die-lun. He's really good. Haven't you heard Bob Die-lun, man?' So we're all goin' around sayin' 'Bob Die-lun,' you know."

Alan painted such a vivid word picture of himself and his friends that I could almost imagine myself there. We laughed uproariously. I wanted to hear more but was mindful that Alan had an appointment in Nashville that evening.

According to Alan, the folk thing had already peaked and he tried to do a lot of catching up. He spent almost the entire summer between his first and second years of art school in his room learning songs out of song books and off records. He did manage to do art work, however. And it still hadn't occurred to Alan to consider a career as a musician.

Alan's art teacher Bill Thomas, whose family was from the mountains of Kentucky, would join Guthrie playing guitar, and eventually Alan joined them on guitar.

"So lunch hour at art school got to be music hour. Bill used to sing all those songs about revenge and (in the song) somebody always got stabbed or something. So from that point on I just kept on buying records."

When Eddie Donaldson decided to open a club on West Washington Street in Louisville, he sold The Shack on Bardstown Road to Ken Pyle (who, with his wife Sheila Joyce, now owns The Rudyard Kipling Restaurant). Pyle turned it into The Roundtable Theater.

"Kenny's room, that's where Sam Bush and (Tim) Krekel and all those people came through there playing; Buddy Spurlock, the banjo player who was real well known in the region back then in bluegrass bands; J.D. Crowe; everybody came through there," Alan reminisced.

Dan Crary, who Alan describes as one of the top flat pickers in the country, also used to come and play there, he added.

"That, to me, is where the Louisville folk scene (was) . . . there, and a little place called Port O Call down on Zane Street. That's where I did my first 'concert.'"

"For the record, The Shack was the first place I ever got on stage and played in public." It was at the insistence of his cousin and her boyfriend. Alan sang "House of the Rising Sun," got offstage, and said, "I'm glad that's over." Alan did confess that he "sorta liked it."

"I played Kenny's place off and on, weekends mainly. A guy who is now known as Lee Clayton would come in there and play. And I still remember one night he said, 'Man, you know, I actually got backstage at a Peter, Paul and Mary concert. I sat back there and talked to them, and they were playing their guitars and stuff,' and he (Clayton) says, 'We're as good as them, we can do this.' He said 'I'm goin to Nashville,' and he did."

Alan's infectious laugh caused me to join in. I laughed even harder as I recalled that Alan had introduced me to Clayton very briefly in Louisville less than a year earlier, and in an interesting bit of business, I ended up picking up his lunch tab. It was, I suppose, "my pleasure," albeit an unplanned one.

Clayton had considerable success in Nashville, earning for himself the title of "the outlaw's outlaw." He wrote the Waylon Jennings hit song "Ladies Love Outlaws," the Willie Nelson hit "If You Can Touch Her At All," and had what has been called "one of the best country albums of 1978" -- Border Affair. Clayton made a lot of money from the Jennings and Nelson versions of the songs, Alan said.

Alan wasn't ready for Nashville at that time. "I was still learning some songs and stuff," he related.

"I made some pretty large steps in my music, I think, from the time that I started playing The Shack to just before the time I got drafted. I went from a hobbyist to getting real serious about it and starting to write a couple songs within about a year's time."

Alan and a number of the other art students always looked forward to displaying their art work at the local St. James Art Fair. Alan also looked forward to the music. Nancy Johnson (now Nancy Barker, organizer of Kentucky Music Week and Weekend) was one of the musicians. "It was great," Alan exclaimed.

About two weeks after his graduation from art school, Alan gave his first concert at Port O Call. "It was at the opening of a one-man art exhibit that I was having . . . it was kind of a neat thing to do at the opening of my show, was to give a little musical concert. It was about an hour and I didn't have any original songs at that time. I was singing Dylan, Lightfoot, a guy named Hamilton Camp (a folk singer) and Leadbelly."

"The concert at Port O Call was well received, every chair was filled, and the owner was happy," Alan assured me.

After the Port O Call performance Alan had a one-man (art) show at the gallery in Louisville's Cinema 3 (now Cinemas 13, more or less).

After graduating from art school, while working at a frame shop, his mother put in a good word for him and he was hired to work in the advertising department of a local discount department store.

He was still planning a career in art (he worked with acrylics and watercolors, doing mostly landscapes, but some portraits when people would ask him to), and "looking forward to every weekend when I could go play music. And it was fun, you know, we'd go down there and we'd drink beer and we'd play music and it was just great."

In the summer of 1966 during a kind of "restless" period in his life (break-up with a girlfriend, etc.), Alan, at the suggestion of his father, decided to visit relatives in New York, just to get away from Louisville. He sold his battered '57 Chevy "for a lot less than I would ever want to admit," to pay for the plane ticket to New York. He intended to check out Greenwich Village "just to see what it was."

"It was the typical (pause, laugh) small-town boy in the big city. And I'd get on the subway every day and go into Greenwich Village and just walk around that place. I saw Jose Feliciano at the Gaslight Coffee House, and that was just incredible. To somebody who was trying to start to learn this kind of music, Greenwich Village in 1966 was really a happening place, but the bulk of that whole folk era had already come and gone there. Dylan and (others of that genre) were off being rock 'n' rolls stars in England. But there was definitely still a folk scene . . . there were just musicians everywhere. And I'd sit around Washington Square with my guitar, you know (laugh), it was funny, really."

Although he was there for only about three weeks, Alan says the experience opened his eyes to a lot of things. He also had the good fortune while there to hear the Rolling Stones live in concert, which was a "real experience."

Watching for another important milestone in Alan's career, I jumped on the revelation that he had started writing his first song while in New York. "Was it (the song) significant at all?" I inquired.

"Not really, because it was to the melody of a Bob Dylan song . . ." (As an aspiring songwriter with few melodies, I found myself laughing heartily, momentarily interrupting his sentence, but he tenaciously continued) "which was, which was a traditional melody that he (Dylan) used to write a song, 'North Country Blues,' and he didn't try to hide that at all. . . . It's the melody of an old Scottish ballad, and that song (Alan's) . . . I don't even know if I ever finished it, to be honest," Alan said.

"What I think of as my first song, I wrote in Louisville after I had come back (from New York) and I was playing down at The Roundtable Theater." The song was called "Afternoon in May."

"Is it in your repertoire?" I jokingly inquired. (I had attended many Alan Rhody concerts and I did not recall the song.)

(Laughing) "No. Nyaah." He did sing it at The Roundtable, however, he admitted.

"And then 'Alice's Restaurant' happened and . . . Newport Folk Festival was a big thing then."

"(Local musician) Mickey Clark was one of the first people that I related to in that phase of music, because I heard him down there (The Roundtable Theater) for the first time and he was singing some of these Gordon Lightfoot songs which I had never heard. And so he turned me on to Gordon Lightfoot and I instantly went out and bought every Lightfoot record I could find, which only consisted of one album at that time.

"The Roundtable Theater was just the place where everybody in folk music would go and play and hang out. And churches got into having folk masses around this time." Alan remembers going on a trip with a friend to hear Don Francisco, who sang "Weeping Willow," and being very impressed.

Alan had registered for the draft (the Vietnam War was going on) and he knew he would be drafted as soon as he graduated. He went to Cincinnati, thinking that he would enrol at either the University of Cincinnati or the Art Academy of Cincinnati, not only to further his art education and eventually get a B.A., but also to avoid the draft, "which was just the way people looked at it," he said, then added with a laugh, "especially art students and musicians."

Having heard about Gordon Lightfoot and the music scene in Toronto from Mickey Clark, Alan had given serious consideration to going to Canada before he was drafted.

He applied for conscientious objector status. It was not an uncommon thing, since so many people were opposed to the United States' involvement in the war, Alan explained.

His application was turned down, and in December of 1968 Alan was drafted as a conscientious objector.

By that time he had married Kathy, and they were the parents of a baby daughter, Bridgette. Kathy was pregnant with their second child.

Alan was a model soldier, he said; he didn't hate the Army, he just did not believe in U.S. involvement in the war.

After two or three weeks of processing at Ft. Knox, Ky., Alan spent Christmas at

home, and in January of 1969 was sent to Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, to be trained as a medic to be sent to Vietnam.

After he had completed his training as a medic, Alan's orders came down and he was scheduled to go to Germany. "And I thought, boy, God is on my side, fate has finally come my way." He would be able to take his family with him. Their second child, a son, had been born while Alan was in Texas, and although he wasn't allowed to come home for the birth, he did get to come home when his son was about a month old.

Alan was still trying to push to do something in the Army that was associated with art, or possibly music. He tried everything, he said. "Well I painted everybody's name on their lockers . . . and then I painted landscapes on the mess hall walls . . . and I was a drummer in the Army." Whenever volunteers were needed, Alan volunteered.

At a Ft. Sam Houston talent contest, Alan won the top prize with his version of Arlo Guthrie's "Ring Around the Rosie Rag." For the contest he had purchased a little black felt derby hat to cover the "buzzed-off hair."

The day after the contest Alan was called to the captain's office, where he was convinced it was his duty to surrender the very large first-place trophy for the company's trophy case. Hoping to stay in good stead with the top brass, he decided he could live without the trophy. They didn't ask for the semi-finals trophy.

When the "actual real" orders came, Alan was called to the commanding officer's office and was told, "Well, Kohnhorst (Alan's name before he changed it to Rhody), looks like your congressman's been working for you, 'cause you're goin' to Vietnam now, as an artist."

When he next went home on leave, up until the very moment (about two weeks later) he decided he was going to Canada, Alan "went back and forth inside my mind hundreds of times about 'Well, I'm going to go ahead and go to Vietnam and get it out of my life, get it over with, come back and get on with my life,' or 'No, I'm gonna go to Canada,' or 'No, I'm just gonna go AWOL and just roam around the country or do something.'"

During that two-week leave, he discussed, only with his wife, the idea of going to Canada.

When he reported back from leave -- to Oakland, Calif. -- he discovered that his orders were for him to go to Vietnam not as an artist but as a medic.

About halfway through processing, Alan strolled out of line and out the Army's front door. Destination: Berkeley, Calif. He visited his cousins there and phoned his wife and parents to discuss with them his thoughts of going to Canada to avoid Vietnam. His father told him that it could be the biggest mistake of his life if he went to Canada, and advised him to think it over a long time before he made the decision, because if he went there it would be "just as if you're legally gone from the United States for the rest of your life." Alan was aware of that fact.

After about a week he decided to go back and process through. At that point the soldiers in his same situation would line up each morning, and, Alan said, "they would call out names, and if your name was called you went and got on a plane and you were gone -- to Southeast Asia." Alan got in that line at least two mornings, and his name wasn't called.

It was then that he decided to apply for a conscientious objector discharge, thinking that even if it didn't work, it would keep him from being put on a plane immediately. At this point, Alan laughs, explaining that he couldn't help but think of "Alice's Restaurant," "because they sent me to see the psychiatrist, they sent me to see the chaplain, they sent me to see the commanding officer, and every one of them encouraged me just to go to Vietnam. And I thought, 'Well, this seems like a . . .' I guess that's where that song, 'It Looks Like A Set-Up,' came from later."

Alan's thoughts did not change. "I was still feeling, 'Well I'm still holding to this I'm a conscientious objector, I was a conscientious objector before I got drafted into the Army, and that's what I am and I'm not going to Vietnam under any circumstances.'" He was treated as a trouble maker and sent to what was called a company of "undesirables," (mostly people who objected to the war and were awaiting the outcome of their various cases). It was in Oakland Calif., run by M.P.'s, and the "undesirables" spent most of their time keeping the place clean.

It was during that time that Alan "had the great experience of going over the Golden Gate Bridge for the first time in my life in the back of an Army garbage truck. That was the big memorable experience I got out of that," Alan laughed.

Every weekend the "residents" were free to go and do as they pleased as long as they came back. Alan believes with all the clerical confusion and heavy backload of cases, etc. the military didn't care whether they came back or not.

After about a week or two there, and with eighteen months remaining in his tour of duty, Alan "made the real decision" to go to Canada. He packed up his civilian clothes and his guitar and took a bus to Berkley, Calif.

He went to a couple of coffee houses in Berkeley and San Francisco and performed at their "hootenannys" (what are now called open stages). He used a different name for each performance, thinking he was AWOL from the Army and that they were out looking for him. At the Freight and Salvage in Berkeley, Alan met a talented musician who, referring to his own guitar, said, "You know what this is? This is the guitar that Jesse Colin Young recorded his first album with. This is his D-18." He asked Alan to watch over the guitar while he prepared himself for his performance by running around the block.

"Right about that time I thought, 'I'm gonna go to Canada and become a musician, that's what I'm gonna do,'" Alan said, "because I know what the art thing is. You've either gotta be in the commercial side of art or else you're gonna starve to death trying to be a painter."

He remembered how the guys in the barracks in San Antonio would get together in the platoon leader's private room and smoke various things and listen to Jimi Hendrix. Alan would play for them. amd he was invited to smoke with them, but declined.

"They said, 'Man, you oughta go to Canada . . . Gordon Lightfoot, look at him, you could do what he does,' and I'm thinking maybe I could, you know." Alan laughs at the recollection, and some of the tension of recalling the whole Vietnam vs. Canada phase of his life seems to be at least temporarily eased.

Alan related that when he called home with news of his decision to go to Canada, "everybody just freaked. They just thought I was making the mistake of my life."

(Within a year Alan's parents were supportive of him. They weren't against him doing it, they were worried about his future, Alan told me.)

I could feel the tension return momentarily, but Alan took a deep breath and continued to relate the steps he took that would represent a turning point in his life, his career plans, and would result in his not being allowed to return to this country for more than six years.

It is important to understand Alan's feelings about the Vietnam war and the people who served in it: "I have a lot of respect for the men and women who did go over there, because they were following their own heart and conscience and they were doing what they thought was right at the time, and that's exactly what I did."

Alan was welcomed into Canada as a landed immigrant because he had lined up a job at a department store, had a wife and children, and would add to the economy of Canada.

In June of 1969 Alan went alone to Canada. Two months later Kathy and the children joined him. Kathy had sold a lot of what they owned in Louisville, and put the rest on a moving truck. A trunk with wedding gifts, new linens, silverware and china and other treasured items was stolen from the truck. They had to start from scratch, Alan said. That was in Vancouver.

Two years later they started over again in Toronto (they lived in three different places there), then six years later they started all over again in Nashville. The love and concern Alan felt for his wife and family was apparent as Alan related the events of that difficult period in their lives. Not once did he attempt to elicit sympathy nor ask me to try to stand in his shoes. It was a time of sharing, and I came away with the utmost respect and admiration for his handling of an unbelievably difficult situation.

Allen David Kohnhorst changed his name in the summer of 1969 when he was in Vancouver and just starting to think about music as a career. People were having difficulty pronouncing his last name.

He was in "a little greasy spoon restaurant" in Vancouver, and he noticed a Credence Clearwater Revival song called "Lodi" listed as a selection on the booth juke box. Alan was interested in the group, and probably played their song. He pondered the song's name. "Lodi," "Lody," then "Rodi" (pronounced "roadie") popped into his head. He started using "Rodi," but soon realized that he had created another pronunciation problem for himself. So he changed the spelling to "Rhody" and shortened Allen to Alan Viola! Alan Rhody.

While in Vancouver, Alan worked in advertising, played some open-stage coffee houses, met Reverend Gary Davis and Jesse Fuller (a one-man band and writer of "San Francisco Bay Blues"). "He was amazing," Alan said. "I've still got a poster he signed for me. It says 'Lone Cat Jesse Fuller.' Those were big moments for me because I knew these people by their records, and these were famous black blues artists that were the real thing . . . Reverend Gary Davis is just legendary, was a big part of where folk music and blues came from."

Alan won a talent contest in Vancouver, the prize for which was a $500 Martin guitar. (Alan never got the guitar. He had to settle with a "pretty shady" promoter for about two hundred dollars or else a couple of the promoter's friends would take care of Alan "real good" so that he "wouldn't even be worried about the contest.")

Alan decided that he would buy himself a Martin guitar with the money. With his Yamaha as a trade-in, he bought a Martin D-28, which he still owns. "So I won half the guitar," Alan laughed.

On the night of the contest Russ Thornberry, a Texan who had been in the New Christy Minstrels while in college, and who had come to Vancouver to write his first album for MCA Canada, was in the audience. Thornberry was asked to get up and perform.

"I was just knocked out," Alan exclaimed. "He was real good. He had a whole lot of Lightfoot in his music, almost too much to do his own thing, but he was excellent at it. Played this Guild guitar."

Thornberry located Alan that night, offered him encouragement, and asked Alan to give him a call. They subsequently became "real good friends." They were living in Edmonton during that time.

Alan wasn't doing much in music when Thornberry called him and asked, "How serious are you about music? Do you really want to leave advertising and start playing music?" Alan replied in the affirmative, but qualified it by saying that he was concerned about supporting his family. Thornberry offered him a gig that he himself couldn't fulfill in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. "It's two nights, they'll pay you $300 and put you in a hotel," Thornberry said. "And that was like three weeks pay, you know, to me at the time," Alan told me. He accepted on the spot. The gig turned out well and Alan was feeling good about it.

By that time, Alan had written about eight or ten songs that he also felt "pretty good about." (He wrote "My Kentucky" while he was in San Francisco during his "in-between stage" -- while getting ready to go to Canada.)

Thornberry came back to Vancouver to do a noon-hour television show, and invited Alan to come along, hoping that Alan could land a spot on the show. A month or two later a phone call from the television people led to Alan's appearance on the network show that played across Canada. "I thought, man this is fantastic."

Charlie Rich was on that show at what Alan characterized as the lowest ebb of his (Rich's) career. Alan remembers that Rich sang his two old, old hits, "Mohair Sam" and "Lonely Weekends." Alan doesn't remember what he himself sang on the show (probably, he thinks, a song that he had written) but he remembers meeting Rich and how "incredible" he was.

Later when Thornberry got his own television show in Edmonton, called "Music '70" (the year was 1970) he invited Alan to be a guest on it.

The show played havoc with Alan's "real" job, and he worked out a deal whereby he could free lance for his employer and continue with his promising music career.

The next season Alan was asked to become a regular on the show, "Music '71," which he did. He considers this his "major move to really full-time music." He did 26 episodes of the television program and "to me, that was some of the first video ever done," he believes, because they were doing songs and then going out on location and videotaping footage and combining the two. For instance, when Alan did Dylan's "Girl From the North Country," they would cut from the studio to footage of Alan and a girl whom they had hired, walking in the snow along a river bank.

During his time in Canada, in about 1972 or so, Lightfoot released "Me and Bobby McGee. Alan thought it was a Lightfoot song, but later learned that it had been written by Kris Kristofferson. Alan said that there had been a lot of talk about Kristofferson in Canada.

Alan decided that if he was really going to get into music as a business he'd have to leave Vancouver and relocate in Toronto. It took two visits there before he decided to make the move. He got another advertising job, for security, and a gig at Steel Tavern where Gordon Lightfoot had played, and "Kathy, again, sold some stuff, put everything in a moving van, and she and our two little kids got on a train and came across Canada. They loved that trip 'cause going across Canada on a train through the Rockies from West to East was great and the kids still remember it." That was in 1971.

Alan worked the day job until he got enough gigs to quit the job and become a full-time musician. He worked a lot of clubs and did five network television appearances there.

Thornberry called Alan back to Edmonton and produced two singles with Alan singing his (Alan's) original songs. One was on the London label which was a major label out of England, and the other was on an independent label that was distributed by London. Alan's "My Kentucky" (a different version of which is on his Border Crossings album) was on the B side of the second single.

Although neither record charted, they did get some airplay, but Alan was at the point where he wanted to put together a tape and start hitting the record labels in Toronto. At the time he was constantly working (which he did for nearly five years straight), in town and out of town. He played everywhere he could -- colleges, coffee houses, bars -- he said.

There was still a healthy folk scene in the Yorkville area of Toronto, and country music was starting to edge its way into the marketplace.

The biggest club there was the Riverboat, and it was there that Alan heard and met Steve Goodman. It was also at the Riverboat that he met the Good Brothers, a bluegrass-oriented band in Toronto that had just made their first album and were starting to make "some noise." They let Alan do a guest set between their two shows, his only time on the stage at the Riverboat.

Later, in the Fall of 1980, after Alan had moved to Nashville, the Good Brothers invited him to be the opening act on their tour from Toronto to Vancouver. They did 28 dates in 34 days. That was his "first real taste of an actual extended, grueling road tour of one- and two-night concerts." It was fun, educational and a good experience for him, and he feels indebted to them for remembering him from his earlier days in Toronto.

In 1975, with the advent of the Ford administration's "alternative service program," Alan was eligible to return to the United States and participate in President Ford's amnesty program and received his discharge on a date that he remembers well. It was December 12 -- Kathy's birthday.

However, since they were by that time settled and happy in Toronto, they decided to stay on in Canada for the time being. Alan would continue his growing music career there.

Alan was performing and listening to the music of Waylon Jennings and Charlie Daniels, who had just made a name for himself in Nashville.

On one of Louisville musician Mickey Clark's trips to Canada (he performed there about once a year) Alan told Mickey (who was playing songs by Billy Joe Shaver and Kris Kristofferson while Alan was singing the songs of the Rolling Stones, John Prine, Dylan and Lightfoot, along with his own material) that he was anxious to come back to the states to see his family and play music. Mickey told Alan about the Butchertown Pub that had just opened in Louisville, and about the Tradewinds in St. Augustine, Fla. (Alan's parents were then living in Jacksonville, Fla.)

By February of 1976 Alan had lined up gigs at Butchertown Pub and a gig in St. Augustine.

On one trip to play at Butchertown Pub, Alan stopped in Nashville to look up friends from Canada who had moved there. He left a ten-song tape at Waylon Jennings' production company, and one at Ray Stevens' studio, "hoping to be discovered." He never heard from either of them.

After one of his Butchertown performances, actress Nancy Lea Owen came up to Alan, told him she liked his music and that she knew someone who was an executive at a radio or television station in Nashville (it turned out to be WSM). She offered to take a tape of Alan's to that gentleman.

After giving the tape to Nancy Lea, Alan went on down to Florida. A week and a half later she called him in Jacksonville (he played two weekends in St. Augustine and visited his parents on off days).

She told Alan that she had given the tape (containing four or five songs, including "Tuesday Night Local") to Elmer Alley at WSM. Alley thought it was pretty good and had given it to Buddy Killen at Tree Publishing. "That was what you would call my biggest break, but I didn't even realize it at the time," Alan confessed.

On the way back to his home in Toronto (where he felt he had achieved some musical success) Alan stopped in Nashville to meet with Killen, who said he really liked what he heard on the tape and wanted to work with Alan as an artist as well as a writer. Alan said he wanted to think about it. Killen showed Alan around Tree. "The walls were lined with BMI awards like 'King of the Road' and "Green Green Grass of Home." Alan didn't realize how big the company was at that time in Nashville. He wasn't too sure about "who they were and what they did." (Who they were was the number one country music publishing company in the world. They still are.)

Killen suggested that as long as Alan was there he might as well "put down a few things" on their four-track recording equipment. They did, and Alan said he would get back with them. "On the trip back to Toronto "Stroke" (Byron Stoehr, who had been playing the gigs with Alan) and I were counting our millions," Alan said. That was in February of 1976.

By April, Alan had decided he would talk with Tree again. He thought he had "not a whole lot to lose and everything to gain." He set up another gig at Butchertown Pub.

Alan ended up signing a contract at Tree on that trip to Nashville No money changed hands at that time. Alan told them that he had a family and wasn't in a hurry to move, but Killen told him he'd have to be in Nashville. Alan returned to Toronto.

For the previous three years (from about 1973 up to that time) Alan had been producing and writing a lot of songs. Upon returning to Toronto, he mailed to Tree reel-to-reel tapes of any new songs he had. Some of the first tapes he sent were sessions that ended up being on the Border Crossings album, which Alan didn't put out until 1986 (10 years later).

On his occasional trips to Louisville to play, Alan would make a trip to Nashville with more songs. About the second time he came down he had written "I'll Be True to You." During a stop in Louisville, he went to the apartment of an acquaintence he had met at Butchertown Pub. Alan told the friend that he needed to get six songs on tape. They "turned the machine on and sang the songs one after another," Alan said, and took them to Nashville. Cliff Williamson listened to Alan's songs.

"I'll Be True to You" was on the second demo tape Alan took to Williamson, who was the first song plugger Alan worked with. They discussed what would be Alan's second demo session at Tree. Cliff listened to the new stuff. He thought "I'll Be True to You" had a good hook line and a good chorus, but was too long. He said Alan would have to rewrite it before it would have a chance at being recorded. Alan agreed to the rewrite, but wanted the original version to be put into Tree's catalog. The song is still there in its original long version.

Alan stayed in Nashville for three days with friends Tom and Judy Newby, working on the song at their home and at Tree. "In the process of re-writing it, the guy in the song was the one who died. All of a sudden it seemed sadder if the girl died," so Alan made that change. He went over to Cliff's house, and he was knocked out by the new version. Alan "kinda liked it, but wasn't as knocked out by it as Cliff was." Alan went ahead and did a demo session at Tree which included "I'll Be True to You," and returned to Toronto.

Back in Toronto, still working, doing gigs, Alan received a call from Cliff in Nashville, who told him, "Man we've got your song cut. This gospel quartet called the Oak Ridge Boys, they've recorded it for what is to be their first country-pop album."

Alan's reaction: "I thought, 'Nobody's ever heard of these guys. I'm gonna have my first song cut by some gospel guys.'"

(To be continued next month.)