social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

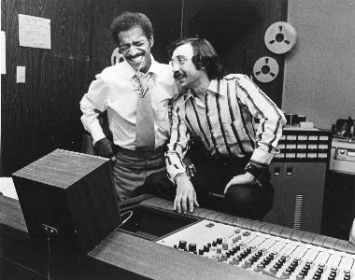

John La Barbera

By Allen Howie

It would be tough to invent a more quintessential American success story for a movie treatment than John La Barbera's. His has the advantage of being true:

A Sicilian immigrant, [La Barbera's father] is raised in an orphanage in upstate New York after his father passes away. In the orphanage, he's given a baritone horn to play. At the age of fourteen, he goes to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad, first as a waterboy, then shoveling coal. He works for the railroad all his life, raises three sons, supports his mother – and buys musical instruments for his family. They start their own band, father, mother and sons, and play for extra money. All three boys become professional musicians and one of three goes on to play with and write arrangements for some of the finest jazz musicians in the world, earns gold and platinum records, and finally joined the faculty at the School of Music at the University of Louisville.

John La Barbera smiles as he tells about his father's first instrument. "He thought he was a king," he recalls, "because, in the old country, only the wealthy could have a brass instrument – string instruments were common." La Barbera's father made sure that his own sons were no strangers to music. "When we were born, we had every instrument of the orchestra in our basement – except for a harp. He made us all learn to play clarinet until we got our permanent teeth, and then we could play anything we wanted. My older brother Pat picked the saxophone. I picked the trumpet. So my little brother Joe had to play drums to round out the family band."

It wasn't long before the quartet became a quintet. "My father used to take us boys out to play gigs as a family band," La Barbera remembers, "and my mother would get left at home. She was very bugged about that. So she went out and bought an upright bass, and made up a fingering chart and put it up above the kitchen sink. As she washed the dishes, she'd memorize the fingering chart. That's how she taught herself to play bass, then she joined our band."

For a young boy growing up in the late 1940s, La Barbera had it made. "We were buying our own comic books when we were six and seven years old. When I was six, I was making three bucks a gig – that was big money." As fondly as he recalls those days, however, La Barbera is honest in his appraisal of the band's sound. "We were awful, I'm sure," he chuckles. "But it was a very strong family unit, and it kept us off the street and taught us a craft. That's what my father could give us, that skill."

Little did the elder La Barbera know how far that experience would carry his boys. "He never thought it would progress to where it did," his middle son admits. "For his generation, you wouldn't believe that you could make a living at music. He was an amateur musician and always played extra gigs to supplement the budget, but he never thought we could make a living at it. So then when we went on to be pros and got all these major things going on, he was really proud.

We fired him when we were teenagers and started our own jazz band."

By their early twenties, the La Barbera boys were playing in some pretty heady company. "My older brother went out first," La Barbera says, "with Buddy Rich's band. Then at the end of 1967 or early 1968, when I was 23, I went out with Buddy Rich's band and became Buddy's personal arranger. I was in Boston at Berklee College when I got the call from my brother Pat and went right out on the road. That began twenty–five years of writing and playing. Mostly writing, because after Buddy's band and the Glenn Miller Orchestra, I really lost my interest in playing professionally. I enjoyed the writing more than playing."

La Barbera's writing and arranging skills brought him to the attention of the best bandleaders of his day. And he's quick to remember who was the most challenging – and rewarding – to work with.

"I wrote for Count Basie, Woody Herman, Doc Severinsen – all the bands – but Buddy Rich came out with his new band in the sixties, so he wasn't stuck with a style. There's a Count Basie style, there's a Woody Herman style, there's a Kenton style – there's even a Guy Lombardo style – and I can write all of those styles and be somewhat creative. But you still have to stay inside that narrow framework.

Buddy didn't care. You could write anything for him. He'd either love it or throw it out. You had total freedom to write whatever you want. For any artist, that lets you be more of yourself than the client. Buddy gave the writer more – and frankly, [he] had such great bands that they could play anything. That's not true with a lot of the bands at any given time."

As La Barbera recalls, Rich liked to mix it up musically:

"Buddy liked shuffles – real backbeat shuffle kinds of stuff. He loved jazz waltzes. And liked suites and really long works – he loved that. He felt he was beyond the three–and–a–half–minute cut. Anything unique and unusual.

I remember one time in England, he wanted a bolero. He wanted to go out there with just one snare drum and a big band arrangement just doing a bolero. He wanted anything that would challenge him.

When you're that good, you don't want to play the same stuff every night. He'd say, 'I want this – and I want it tomorrow!' Or, 'Give me a chart on Mission: Impossible, or whatever – he knew what he wanted."

According to La Barbera, Rich's skills weren't limited to his drumming. "He was a good editor," La Barbera notes. He didn't have the musical skills to say, 'This is wrong here, here and here.' He'd just say, 'Cut that out, cut this out and put those two together – that's what I want.' Good editing skills – that comes from vaudeville, I think. He was a genius from playing all those years. That was the most fun."

But if his tenure with Rich was productive, the bandleader could also be firm. "Buddy was probably also the toughest to work for," La Barbera states of his former boss. "He knew when to be mean. You have to realize that he grew up in vaudeville and had been taken advantage of all his life. He was a very insular person – that's a wall you put up when you're trying to protect your own interests.

He was the most difficult to work for – but the most rewarding. You don't mind writing for someone like that. At the moment, you might grumble, but you don't mind in the long run."

La Barbera's own experience in the years that followed gave him a renewed appreciation for Rich's tough demeanor. "As I get older and work with bands – I'm the co–founder of Diva, which is the all–woman jazz big band in New York – when you finally have a hand in actually running a band, I can see why he was such a screamer and yeller. You get fifteen musicians in any one situation, and that's the last place you want to be in a position of leadership."

La Barbera observes that, once a writer's name gets circulated, the work finds him (or her). "It's like any field – we all know who's doing what. It's a very small world. You can't sneeze in Louisville without someone in L.A. offering you a handkerchief.

No matter what field you're in, everyone knows what's going on. And in the music industry, there's a very close network – people know what's going on. We all have a reputation, and it's very easy for people to find you. So you build up your regular clients – once you're known for one thing on a record, someone'll say, 'I want this guy.' and they'll get you. It's easy to maintain your visibility," he acknowledges, "but you still have to be out there hustling all the time."

Even though most of La Barbera's clients were in the Big Apple, he refused to live there. "I never liked New York City itself," he admits. "My work would come from there, but I never wanted to live there. I lived away from New York City in a small country town as a writer before we came here (to Louisville).

I think I was one of the first writers to prove that you could do it outside the city. Today, it's commonplace to have a home office and a fax and overnight mail, but before all that, I had to convince clients that I could have the work done, and that I didn't have to be right down the street in the Brill Building.

It took awhile to build that up, and I did local and national accounts, and did quite well. But I always kept my focus in the arts and in the jazz world as opposed to selling out and being commercial."

His line of work required not only producing arrangements of existing material, but also writing original compositions. La Barbera still finds the latter more difficult than the former. "It's easy to write an arrangement of something that already exists," he explains, "because you've got the foundation. But human beings are strange creatures. We love rules. The more rules, the easier it is to survive. Take away all the rules, give us total freedom, and we wouldn't know what to do.

So when someone says, 'Write me something.' we say, 'What? How long? For what?' So it was more difficult to write something new with no restrictions – although I was young and foolish and didn't know any better.

I took a lot of chances," he says somewhat wistfully, "more than I would take now. As you get older, you become your own editor. The more life experiences you have, the more you edit yourself. Sometimes, I don't think that's good. But you can't help age, you know – the beard gets grayer."

La Barbera's reputation led him to some lucrative and interesting gigs with some of the most well–known musicians in the world, including a famous commercial with the late Sammy Davis. "Working with Sammy was quite an experience. We did the 'plop, plop, fizz, fizz' (for Alka Seltzer). That was a whirlwind – Madison Avenue advertising at its upper level. We're talking hundreds of thousands of dollars spent to use a major artist to promote Alka–Seltzer tablets that probably cost about two cents."

But arranging for a commercial, La Barbera says, is hardly a liberating experience. "The person who does the music for any advertising is totally subservient to the ad agency. The agency tells you exactly what they want. You cannot go beyond those boundaries. And if you're smart, you'll listen very carefully to what they've planned. This is not a roll of the dice – everything is really well–researched.

I'll give you an example. We did 'plop, plop, fizz, fizz' with Sammy.

We had one of the biggest recording studios in New York City with a full orchestra. The New York Symphony string players [are] on the floor. Who's who in New York City studio players [are] on the floor.

I'm standing there. I had written the arrangements the night before, because the advertising agency keeps changing its mind right up until the last minute.

I had gone to use my brother's loft to write the arrangements, and (legendary jazz trumpeter) Chet Baker was there with his girlfriend.

I was so in awe of Chet Baker that I couldn't write in front of him, so I left. I went to my copyist's place and wrote the arrangement.

We prerecorded the full orchestration. We were also doing a phonograph record at the same time that they were going to give away free through Reader's Digest or something.

At this point, forget the advertising budget – the music budget alone may have been a hundred grand, two hundred grand. Sammy Davis wasn't there – he was at Caesar's Palace in Las Vegas.

They said, 'We need someone to go to Vegas and put Sammy's voice on.' The person who was supposed to do it was so afraid of Sammy Davis that they had no one to go."

La Barbera sensed an opportunity, and seized the moment.

"I had worked with him before and said, 'I'll go.' So I went out to Vegas and spent a week free, because he didn't want to sing for a week."

Davis' reluctance to perform wasn't the only problem La Barbera had to contend with. At the last minute, the agency changed one of the lines in the spot, even though the musical background was finished.

"When you write a song, you have lyrics against music – it's set. There was a phrase in this one, 'when your head and stomach.' A telegram came from Germany or New York to the agency saying that we had to add the lyric, 'aching head and stomach,' because aspirin was involved in Alka Seltzer. So at the eleventh hour, with everything prerecorded and preset, we had to make that change."

Davis finally showed up, and the spot became part of advertising history. "Sammy was a good singer," La Barbera acknowledges, "but it's interesting that when you get an artist away from their domain, they become very difficult to work with, as do other people. I tell my business students that most of your job is being a translator and a mediator among people who know nothing about what you're doing – but think they do."

In spite of its downside, La Barbera finds commercial work less taxing than more artistic endeavors. "It's much easier to get a good take with a commercial than with a record. With a commercial, you're not worried about a creative or an emotional presentation. You're worried about a very specific mechanical replication of what needs to be done.

You're not so concerned about the masses warming themselves to a particular product, because the music is not the primary focus. This is selling the product. It's got to help sell the product, but it can't take the focus away from the product. Plus, you're dealing with the highest–paid studio musicians, and you know they're not going to make mistakes. You don't have any problems. You get it done. And there's very little decision–making on your part, because it's all cut and dried. In an emotional setting like a record, they'll say, 'That's not a bad take, but let's try this one, and then you have to make decisions. So commercials are easier."

One of La Barbera's career highlights came courtesy of his work with the Glenn Miller Orchestra. "I've been associated with the Glenn Miller Orchestra for a long time," he relates. "When Glenn died, his estate never wanted any 'ghost bands.' Finally, Helen, Glenn's widow, decided she would allow a band to represent the Glenn Miller Orchestra for the estate, and that's been going on ever since."

La Barbera did a lot of arranging work for the resurrected group, scrupulously capturing the Miller sound in his charts. "I honed a lot of my skills writing for the Glenn Miller Orchestra. One of the nicest things to come out of that is this Glenn Miller Christmas album that we produced. Two fellows and myself who were on the Glenn Miller band, along with Richard Wilhoyte of Kentucky, produced In the Christmas Mood.''

The album, which led to two of the highest achievements of La Barbera's career, also gave him an unexpected dose of reality each time.

"It went gold a year ago," he said, "and UPS left a platinum record at my door last week."

I was telling my wife when the gold record arrived a year ago, they left it against the door, and I said, 'What? No ceremony?' You expect someone to take your picture and hand you the record."

But I get this box, and there's a gold record with my name misspelled."

I sent that in, and they changed it, then I hung it on my wall – I'm very proud to have it, because it's one of the nicest productions I've done. Then last week, they leave the platinum record leaning against the door – but my name was spelled right. That's a million records. That Christmas record really struck a chord."

Christmas albums are notoriously difficult to assemble. Any artist can record a batch of Christmas songs, but to capture the essence of the holiday on record is another matter entirely. La Barbera credits his success in this area to fidelity to the Miller legacy. "I hired another arranger to help me out and worked from the premise that Glenn never died, that he came back from World War II, that it was now the late 1940s, maybe 1951 or '52. I only picked tunes that met that criteria. I arranged everything as if Bill Finnegan or Billy May had arranged it for Glenn."

For this recording, La Barbera made sure that he kept his own personality submerged, and let Miller's spirit infuse the recording. "I kept my fingers away from things I would have preferred to do, and arranged it in the exact style so that you can't tell wasn't done by those people. I was very religious about this, and the other arranger tried to do the same thing."

La Barbera reflects on the key element in the album's success. "We captured a flavor from my childhood. That's what's difficult about Christmas albums. I think we all base things on what we remember as being Christmas, and our generation is probably the masses. People who don't know that period don't have that foundation to build on, I guess. Everyone tries a Christmas album – Wynton Marsalis, everybody tries one. Very few people succeed. But this one really took off." He grins somewhat ruefully. "I just wish they'd hand me the (platinum) record and take a picture."

Nevertheless, most of La Barbera's memories of a quarter century in the business are fond ones. "Dizzy Gillespie was a joy," he remembers, "one of my good buddies who I loved to work with. Best musician I ever met. Great piano player. Brilliant. And a great educator," the U of L professor points out. "He could articulate everything he knew. Just a gentleman and a lot of fun.

Woody Herman was probably the ultimate bandleader, and the friendliest, nicest guy. He could be hard and really give you that glance, but he was like a 'road father' – he was the most understanding of the road musicians' plight, having been there himself. He wasn't in it for himself, wasn't as selfish as a lot of bandleaders were. Count Basie was another gem, and a great man to work for. Maynard Ferguson was fun. A little on the crazy side – but we all are. High energy."

La Barbera's diverse background, and especially his advertising work, has also given him the chance to work with plenty of performers outside the jazz world, including forays into country and western. "I've worked with a lot of commercial people – Tom T. Hall – you name it, I've done it. They hired Tom to be the spokesperson for Gould's Pumps, a major pump manufacturer for farmers. I had to write the song and get him to fit with this advertising campaign. I'd never worked with him before. It's amazing how easily you forget that all musicians are musicians. You think, well, Tom T. Hall is this, or Mel Tillis is that, or whatever. But they're all musicians, and it's so easy to work with pros. It seems to me the people with the most difficult attitudes are the less–talented people – or the least professional. They try to make up for a lack of talent with a lot of tantrums."

While working in the New York setting, La Barbera met another commercial writer and arranger who would soon go on to bigger things. "Barry Manilow and I had the same office in New York when he was doing commercials. We had the same copyist. He was doing McDonald's commercials back then, probably at the same time I was doing the Alka–Seltzer spot. He was just starting to break away from that and become a soloist."

But La Barbera is unflinchingly honest about his own – or anyone's – ability to predict stardom. Speaking of Manilow, he admits, "I wouldn't have guessed in a million years that he'd be so successful. You can't. You wouldn't even think someone like that had the aspiration. I'd be lying if I said you could tag it, because you can't. Many times I've seen an artist – a young kid – come out with a phenomenal record and realize it was the same kid I heard years ago. You think, 'What happened to them?' But people get it together."

In an arranging career full of stellar achievements, La Barbera acknowledges a few favorites. "The record I'm most proud of is a (Buddy Rich) CD called 'Time Being.' It was originally called, 'Buddy Rich – Stick It.' That was the most fun. And the Christmas record, that was the most personal. I got to do so much on that one.

And Bill Watrous' 'Tiger of San Pedro,' which was a big album for me – I think we really did a good job on that one."

What makes a recording special? "When you listen to it after fifteen or twenty years have gone by," La Barbera speculates, "and you don't think of it as being juvenile or dated, it's a good record. There's a lot of things I've done that I play back now and think, 'Boy, I really didn't know anything back then.' But certain projects don't have that feel – they're almost timeless. That's how I judge my own work."

But all this talk of writing and arranging ignores La Barbera's considerable talents as a trumpet player. "As a performer, in college," he remembers, "we always had small jazz combos. While I was in college, I worked in the horn sections of Gladys Knight and the Pips, Martha and the Vandellas, Otis Redding, the Capitols. They always picked up their horn sections in the town they were playing, and a good friend of mine, Joe Calo, and I happened to be the horn section of choice when they came into Boston. Another group I enjoyed a lot was the Three Degrees – very well–liked in Europe, but never reached the popularity of the Supremes here in the States. So I worked with those bands as a horn player. It was very hard work.

Then I went out on the road with Dick Haynes, Buddy Rich, the Glenn Miller Orchestra, plus odd jobs here and there." Before long, though, the reality of life on the road set in. "I realized when I was 26 or 27 years old," says La Barbera, "what it would take to make a living as a trumpet player on a daily basis – club dates, commercials, occasional jazz gigs – so it wouldn't be as much fun as having the reins. And not wanting to live in the city, the only option was to a writer.

But the playing was fun – no question about it. I still play. I'll go out and perform with a college ensemble – I can get through a set, maybe. But it's difficult to keep your chops up when you're teaching and writing all the time. I'm finding a little more time to play now that I'm here in Louisville. I don't even play in the Community Big Band – I just conduct. Although I'd like to play more. I've been invited to come down to the Seelbach and play one of these weekends, and I intend to take Dick Sisto up on that when I get the chance. But I've gotta make sure I'm really ready – I don't want to go in there and embarrass myself in front of my students."

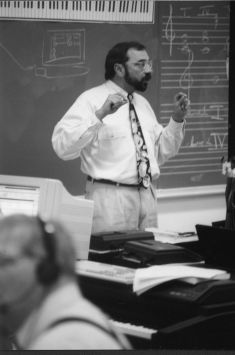

If it seems a sudden transition from the heady environs of arranging for the industry's leading lights to the calmer world of academia, La Barbera dispels the notion quickly. "I've always been in education," he points out. "Even when I left the road to be a writer, I was always closely connected with a university or teaching institution – Alfred University, Cornell University, Eastern School of Music, Ithaca College – I've always been an adjunct at those places."

What, you might ask, entices a player and arranger to teach? "I've always enjoyed imparting knowledge," confides La Barbera, "and I'm lucky in that I can articulate what I know. I found early on that, by being forced to teach what you think you know, it makes you really understand your subject. You may think you understand a subject until you try to teach it – it really shows you what you do know. It makes you more attuned to your field, and clarifies what your skills are. That really is the secret of teaching – it keeps you sharp.

You put something on the board, and a student says. "Why did you do that?' You can't just say, 'Because it looks like it works.' You have to figure out why it works, and then tell them. By making you analyze your own skills, it makes you a better teacher, and by becoming a better teacher, you hone your skills."

And unlike many in the music business, La Barbera harbors no secret fear of computers. "The main reason I know about computers," he admits, "is that, when they reared their ugly heads in the 1980s, you either had to embrace that technology or go out of business. You cannot ignore new technology in any field. I was one of the first to embrace that, knowing the value of it – not to put musicians out of work, but to make my job easier."

La Barbera quickly realized just how much the new technology could relieve the more tedious aspects of arranging. "I'll never forget the first night I left my studio, pushed a button, and my computer starting printing out all the parts for a recording session the next day. I went to bed that night, got up the next morning, picked up the parts and went to the studio. In the past, I would have been up all night long, copying parts, knowing there may be some mistakes – and so, to me, that was a milestone."

La Barbera tries to convey his enthusiasm for the electronic age to his students. "Now I teach the use of computers in music at U of L in writing, arranging and playing. Adults in the community come in to get a reinforcement of what they knew when they were younger, and to get just a little edge on their skills. The music they have in their heads, they may not be able to replicate on a keyboard in live time. Computers help them get that material out so they can hear it. It really is a great tool – a wonderful tool."

La Barbera is also brutally honest about how the business works, and where computers fit in. "In the teaching field or the arranging field, you can't survive without computers. In the classical, orchestral field, music that isn't already in print and ready to be read does not get performed. No more do orchestras have the budget to give you $30,000 to have your charts copied for your symphony. You now have to be your own copyist, and computers are the tools that allow you to do that. But if you don't have the creativity to begin with, the computer is not going to spit it out at you."

But the computer classes aren't his favorites. "The most fun to teach are the arranging courses," he acknowledges, "because they hear immediate results when we play their arrangements back. The most satisfying is the music industry course, where I teach the kids about copyrights, the music business, contracts, how things work – and see them wake up to the fact that this is a business. They become savvy, so I know when they go out the door, they're not going to be lambs ready for the slaughter. The problem is that our industry changes every day, because of computers, the internet, the mechanics and technology involved – it's hard to keep up."

And although he's best known in the jazz arena, La Barbera keeps an ear tuned to the rest of the musical spectrum. Often, he's not crazy about what he hears, as in the case of rap's use of sampling other, older records. "With sampling, there are two things at work. First, unless the samples are cleared, it's totally illegal. The rap artists have predicated their whole art on the notion that they can steal or sample other people's rhythm tracks. Forget whether it's art or not – unless they clear the samples, it's stealing someone else's work. I don't buy it. I know it's a huge moneymaker, but James Brown made a fortune just suing the people who sampled his stuff. And I'm glad.

But more worrisome to La Barbera is the surfeit of new writing or playing when artists rely on samples. "You're lacking a creativity of your own – you have a crutch there that you can't do without. Everyone keeps predicting the demise of rap – it's not gonna go away. But I'm hoping that those who survive will survive by becoming more creative and working with their own material. People who sample say they're paying homage to the past, but basically, they're lazy, and they don't want to do anything on their own. It's holding them back."

Nashville doesn't fare much better in La Barbera's analysis. "Today's country music is not country music whatsoever," he suggests. "There are more Los Angeles executives in Nashville than there are Nashville people. It's a very supercharged pop music.": And La Barbera suspects he knows the reason for this shift. "Basically, the boomers are remembering their days in the sixties when they could hear the melody, they could hear country rock, so now they're listening to this music that comes out of Nashville that they call country, that's melodic and lush and very well–produced.

But traditional country artists will tell you that it's not country. It's this uptown stuff, and it's big business, but it's not country. It's very contrived. You have the right size hat, the right look, the right boots – it's show business. And it's always been show business, but when it started making big money, the big time moved in.

Willie Nelson could never get in the door if he were starting out now. And Willie's a jazz lover. The reason it took him a long time to get connected is because he had too many chords in his music – he was too hip.

Merle Haggard makes jazz albums. The best musicians don't pigeonhole themselves. I'll bet there are a lot of closet jazz fans in Nashville. Not that jazz is the ultimate, but good musicians are good musicians. They'll listen to Berlioz and they'll listen to Bird and they'll listen to Merle Haggard and Bill Monroe."

Rhythm and blues also receives some scrutiny from La Barbera. "What they call R & B today," he points out, "they're using the term, but they're not playing the music. Frankly, if you talk to someone older than us, R & B is not Motown records – it's the original rhythm and blues which begat jazz. To some folks, R & B is Jimmy Smith or Jack McDuff or the organ trio. So these terms are evolving all the time."

When La Barbera contemplates the state of the music business today, and what it takes to succeed over the long haul, he finds it difficult to be optimistic. "We don't allow any middle ground with our artists – we don't allow them to grow and mature. With any kind of music, you'll have the young hotshot that comes out at nineteen years old – the classical pianist, the cellist, the country star with the big hat – and they are hot for a couple of years. If they've got the legs, they'll continue to work, and their popularity will wane, and someone else will come in. But if they can hang in there, then they'll be a legend at the other end. We revere our legends, but we don't help them get there – and that's true in any field.

Record labels used to think long term. But today, they don't work their artists, and they don't think long–term. The Japanese think a generation ahead, and we think ten weeks ahead. The majors want you to produce, and then you're out – they don't look toward the future for their artists. I feel sorry for the younger kids, because they don't have that nurturing. You can't get it the first or the second time. A very patient record company could really reap big benefits by working with artists until they come along. A perfect example of that is Bonnie Raitt. She's been a talent all her life, but her record company stuck with her and her career grew slowly. But now, if you don't hit for your record company after your second record, you're out."

When it comes to jazz, though, La Barbera holds out hope for a bright future. "I think if there's a renaissance in jazz, it's because the population is aging, and they're not satisfied with bubblegum anymore – they want something a little more substantial. So they're listening to more classical and more jazz. I don't know if they're in the clubs – I don't think so – but the whole jazz atmosphere has changed. You can watch jazz on A&E, so you may not go down to the Rudyard Kipling or the Seelbach Hotel. But more people are listening to jazz, and the term itself is broadening. Some people call George Winston jazz. Some people are at the other end of the spectrum and say, 'No, Ornette Coleman, that's jazz.'"

But while La Barbera undoubtedly has his own definition, he leaves the door open – and for a very practical reason. "Whatever brings them into the halls – I can't put anything down. If one person in the audience at a Yanni show decides to look into this more and explore jazz, that's great. I think it's healthy, and I think it will continue. Because jazz is art, and that's why it's survived this long.

When I was growing up, you couldn't buy a bad jazz record. Every jazz record was good. Today, my gardener has a CD – everybody's got a CD out now. There's so much junk out there, you've got to wade through all this garbage to find something that is good. We never had that problem before, because there was not the luxury of self–promotion – you couldn't put your own record out.

La Barbera is enthusiastic about the audience for jazz in Louisville, and pleased with the caliber of players he finds here. He sees his work with the University of Louisville as an opportunity to encourage both. "The jazz audience in Louisville is an older crowd, and they're more traditional in their tastes, based on who we see come in during Jazz Week at U of L every February. We try to gear our presentation toward all ages, and I see our better attendance with the more traditional artists. We try to bring in some younger artists to help broaden that base. I'm not sure it's going to work, but I think ultimately we'll introduce some younger folks to jazz. This year we've got Mary McPartland and Clark Terry coming in. But we're also bringing in a very good singer named Kevin Mahogany, so we're hoping to broaden the base there.

There are quite a few younger players in town. There are some students at Bobby J's who are excellent – that's a hot band. We've got Dick Sisto bringing in many guest artists for all kinds of age groups at the Seelbach.

La Barbera is quick to assert that Louisville is a great place for a novice to explore jazz. "I would say, all in all, Louisville is right on a par with New York or Los Angeles. Per capita, for players, there's more jazz here than in New York City. I can say that without hesitation."

His advice to the uninitiated? "If someone wanted to check out our jazz scene, first I'd send them to the Seelbach, then to the Twice Told Coffeehouse, which has a new jazz policy with no smoking – Jamie Aebersold and Steve Crews were just there. Then I'd send them to the Rudyard Kipling and Zephyr Cove, and finally to Bobby J's, which is a little more hard–hitting, pop–oriented stuff. I know I'm forgetting some, but that would get a person started."

And he's equally quick to include the University in his list of essential listening. "At U of L, we've got Jazz Week scheduled again. We've got a couple of big band recitals scheduled in October and November, Jazz Ensembles I, II and III, the Vocal Jazz Ensemble. We're also doing Mary Lou Williamson's Jazz Mass twice in October. We're going to premier that October 13 and October 20 at St. Augustine Church, . And Dave Weckl, a good jazz drummer, is coming to town for MOMs Music. We're doing a major dance on October 18 at Masterson's during Town & Gown Week with my Jazz Ensemble I, Vocal Jazz Ensemble and Jazz Ensemble II – a real fun jazz dance, swing and big band stuff."

All this from the son of a Sicilian immigrant railroad worker who was determined to kindle in his sons a true passion music.

Only in America.