social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

What Is Bluegrass?

By Bob Babhr

In every style of music, there are arguments among its fans. What is pure blues? What makes something jazz? Is this song really "classical" music? The questions are spurred by the subjective nature of music; not everybody hears the same thing when music is played.

But the arguments over what constitutes bluegrass music seem to boil a little more violently than the arguments in most genres. Even the bluegrass fans who don't get their hackles up high over the issue have a definite opinion. Why the passion?

The debate may rage because bluegrass fans are possessive about their music. Or fans may feel confident about their definition of bluegrass because the music's origins are just 50 years old and clearly documented. Perhaps the subject is debatable simply because the scope of bluegrass has remained small in comparison to other popular music styles. For instance, country music purists may have objected to the first use of drums in country music, but the popular tide has swept away their protests and now drums are essential. Bluegrass has occupied a calm niche in the music world … calm when viewed from the outside, bubbling with friendly arguments within. Variations on bluegrass have sprung up from the very beginning, but none have taken over to chart a new course for the music. The tent just gets bigger, encompassing all.

What is bluegrass? We asked over a dozen spectators, players, movers and shakers in the bluegrass music industry that question and their replies only enriched the debate. Most everybody agreed on one thing, though:

It all started with Mr. Monroe

"Bluegrass didn't start out being called bluegrass,'" said Doyle Lawson, a mandolin player and the leader of the group Quicksilver, which is known for putting the sound of a gospel quartet into bluegrass. "That term was added to it. Bill Monroe had the first band that played the music as it is known today and his group was called the Blue Grass Boys. That's how it got the name."

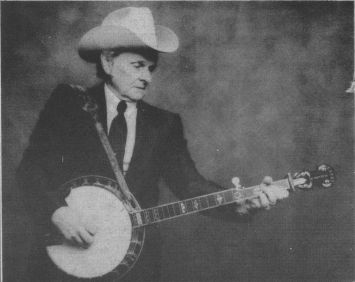

William Smith Monroe did indeed take the sound of a mountain string band, wed it to African-American blues, inject it with high-octane tempos and give this new mixture its name. Scotch-Irish fiddle music and improvisational jazz influenced the new music and the hardship of Appalachian life colored the lyrics. Monroe formed the Blue Grass Boys in 1939, but the prototypical bluegrass sound arrived in the form of Earl Scruggs in 1945. The banjo player from North Carolina championed a three-finger style of playing that made the banjo a rhythmic powerhouse. For many purists that configuration of the Blue Grass Boys, which also featured Lester Flatt on guitar and Chubby Wise on fiddle, laid down the rules for bluegrass, now and forever, amen.

Others say that the early work of bluegrass pioneers such as the Stanley Brothers and Blue Grass Boys splinter group Flatt & Scruggs equally define the sound of bluegrass. There's at least one person who disagrees with that stance. His name is Ralph Stanley and he and his brother Carter led the Clinch Mountain Boys in the mid-1940s, first as disciples of the Monroe sound, later as progenitors of a blend of bluegrass and British mountain music with often-sad themes of loss and alienation.

"Actually, to me, Bill Monroe is bluegrass," Stanley said simply. The fiery banjo picker did make the distinction that he and his still-active Clinch Mountain Boys play "old-time mountain music."

Peter Kuykendall, the editor of Bluegrass Unlimited and a mainstay of the bluegrass music industry, acknowledges bluegrass' debt to Bill Monroe, yet sees a place for progressive and contemporary styles. Monroe's style is the first, but not the only.

"Bluegrass isn't Bill Monroe," Kuykendall said. "It's like saying rock 'n' roll is Elvis."

Funny he would mention Elvis Presley. Rock's first superstar had very definite roots in bluegrass music.

"It's a point of great pride among bluegrass fans that one of Elvis's first records was a bluegrass song," said Dan Hays, the executive director of the IBMA (International Bluegrass Music Association). Even Monroe himself is proud that the King's first local hit had the Monroe composition "Blue Moon of Kentucky" on its flipside. (The other side was Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup's "That's All Right.")

"He come to me and talked to me and apologized for doing the number that way," said Bill Monroe. "I told him that if it gave him his start, that I was for him 100%. He really sold a lot of them. He died awful young, didn't he?"

Bluegrass survived that touch with the rowdy, electric, new style of music called rock 'n' roll, though it lost its primacy on the pop music charts. Monroe didn't change his sound to cater to any new trend, though. He just toured harder. Along the way, his band became a bluegrass farm team that cranked out future stars of the genre.

"Early on, what was bluegrass music was defined in bluegrass purists minds as Bill Monroe's music," said mandolinist / fiddler Sam Bush, a progressive bluegrasser with deep loyalties to traditional bluegrass. "It's so traceable to Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys. To some, that music has never been surpassed. There have been many offshoots; for many acts that was the springboard for their music. Flatt & Scruggs, Jimmy Martin, Don Reno, Sonny Osborne, Carter Stanley, Mac Wiseman— they all were Blue Grass Boys. It's pretty amazing how all of it is still directly traceable back to Bill Monroe. You can see the Monroe influence, but they went on to form their own music."

Monroe himself doesn't shrink away from claiming bluegrass music as his own.

"Oh yeah. I know that I started it," said Monroe. End of discussion.

Is it the instruments?

Bluegrass fans generally agree on what instruments are needed to make the music, but deviations from the traditional four are hotly contested.

"To have it right, it has to be the way that I played it from the beginning," said Monroe. "Play it and sing it with the old-time style that I put in there, the high-pitched way of singing. There are instruments that wouldn't work too good in bluegrass because they would change it into another style. The way it should be kept is the fiddle, mandolin, banjo, guitar and bass. There's a lot of people all over the world that knows that that's what they should play and how they should play it, with instruments like that. Electric bass?

No, I don't think it would work."

Many groups have bowed to convenience and left the "doghouse fiddle" or "bass fiddle" at home. An acoustic bass is bulky and heavy, with a sound that can be difficult to project across a festival lawn. But plugging an electric bass in can rile purists faster than you can say, "heresy."

The dobro is an acceptable addition, as well as supplemental fiddles. Drums are forbidden; the accordion is tolerated because Mr. Monroe once used one in an early version of the Blue Grass Boys (played by a woman, no less).

"Bill Monroe is one man who strayed across bluegrass lines many times," Dan Hays pointed out. "Accordion, other things that were popular to do when they were done. I guess over time you eventually settle into a niche and then whatever you do is okay."

Gary Loeser, program coordinator for Otter Creek Park in Brandenburg, Ky. and the organizer of the park's annual Memorial Day bluegrass festival, insists on the presence of a mandolin. Loeser is a relative newcomer to bluegrass who sees the music's appeal to young people. Instrumentally, Loeser says the traditional four pieces need to be there, but most importantly, they need to be acoustic. "It's porch-pickin' music," said Loeser. "Effects like reverb ... then you're creating music that is electronically tricking you."

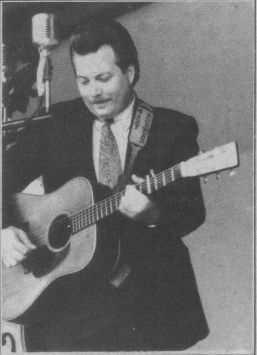

Louisville bluegrass musician Gary Brewer concurs.

"The shortest definition I can give to bluegrass music is I feel like it's all-acoustic music. There are people using electrified instruments, but to me the authentic and strictly bluegrass is all acoustic."

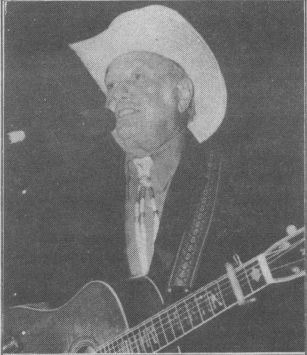

Brewer is a staunch traditionalist who will be performing with Bill Monroe at the Grand Ole Opry in September. His Kentucky Ramblers band, a traditional group that plays original compositions, records for the Copper Creek record label and is a major draw in the region.

Peter Rowan is a former Blue Grass Boy who has made his own way since leaving Monroe, incorporating rock and Spanish music into his folky bluegrass. He still loves the traditional sound though.

"I take great pride in being a Blue Grass Boy," Rowan said. He and 15-year-old bluegrass banjo sensation Josh Williams agree that the banjo is the key to the bluegrass sound.

"It's got to have the banjo," Williams asserted. "A lot of people may think I'm saying that because I play the banjo, but I really do believe it. It needs the fiddle too. It's mostly acoustic, no percussion or anything like that. It's music that's more based on soul and how people feel."

"It's based around that Earl Scruggs banjo playing, that's the foundation, along with the old-time guitar playing," said Rowan. "The banjo is usually the key to that hard-driving style, then everybody has to be in that high gear. Then it's solo, trio, quartet singing.

Berk Bryant hosts a widely enjoyed bluegrass radio show broadcast from Louisville, Ky. and writes a monthly column for LMN, but he prefers to think of himself as a devoted fan of the music rather than an expert. Nonetheless, he was forthcoming with his definition of bluegrass. Using the right instruments isn't enough, he said.

"Just because you have a banjo or a fiddle doesn't make it bluegrass," Bryant said. "There's a lot that's being called bluegrass that shouldn't be called bluegrass. Bluegrass to me has a distinctive sound. That's why it's something you can't really stretch, because if you do, it doesn't keep it bluegrass. I'm a traditionalist, you ~know."

We know.

Examining the intangibles

Several musicians and other pundits discussed the more esoteric traits of bluegrass music. Several people interviewed placed the seat of bluegrass in the heart and soul. For them, it isn't as much being true to a historical form of the music as it is simply being true.

"I think bluegrass is just music," said Gary Loeser. "But I think it's got to have truth. That's the thing that gets me about bluegrass. Four years ago, I didn't even know anything about bluegrass. And I didn't care. But when I started working with this festival and became a part of the industry, began listening to the music, there's something about that that just grabbed my soul. The stories that the songs tell, the chemistry between the vocals and their instruments, the ability that it takes to play the music. It's music at its purest. If you honestly give the music a listen, then you will walk away inspired.

"Bluegrass is soul music. It is inspirational, it comes from the heart. Bluegrass is happy music with sad words. It makes feeling bad feel good."

Echoed Doyle Lawson, "It has to have soul. You have to play from the heart.

You have to feel it before you play it."

Peter Kuykendall joined the chorus.

"Soul," he said. "Honest soul. If you get too over-produced with it, you don't get the soul. It's also an improvisational music. They've come up with an arrangement and improvise within that," Kuykendall said as he watched a band play on a nearby stage. "The country bands just duplicate the albums."

Fiddler/singer Laurie Lewis calls herself "a traditionalist in terms of what I like, but in terms of what I do, I'm not. I bend [bluegrass] to suit me." She emphasized the music's original diversity.

"My definition is a little different, I think," said Lewis. "it's music that takes various traditions and styles and melds them together. Bill Monroe did this, he wrote his own music that draws from various rural roots and spoke specifically to himself. Basically, it's a singer/ songwriter with a string band with various rural music influences. I think it's also the interplay of the instruments up there," she said, motioning to a bluegrass festival stage. "And those real open chords, you got to have that."

Gary Brewer took the home-and-hearth approach.

"I feel like bluegrass is a clean music and that it probably is the most soulfulf eeling music. It seems like the people that are in bluegrass, more than any other, have lived what is in their music," said Brewer.

"It's a heritage," he continued. "It's something that's sustained through this region of land where the roots of the music are. Back in the old days, they called it mountain music or hillbilly music. But we're still talking about the same thing. Rural, farm music. It's just something real. It's real music. There's nothing much altered from the original plans when it come down the pike. There's people that fancy it up and play it a bit more contemporary than other folks, but they're still carrying on the heritage of our music," he said.

There ain't nothing to it, according to Peter Rowan—as long as you know the catalog and have the chops to play it.

Rowan stressed the high standard of musicianship that is constant in bluegrass music, then simply said, "If you know 30 traditional tunes and your playing is up to it, you'll be playing bluegrass."

Bill Monroe had some more specific advice.

[You've] got to love that melody, that sound of the music and the old-time way of playing the music. [You've] got to know how to have that feelin' on it," said Monroe.

It's a high, lonesome feeling, but one of pride and vigor. It's flavored by a fear of God and it's as honest as the hiccups. Bluegrass connects with its audience through that honesty.

It's also a very family-friendly genre of music. Leave it to a fan to center on the one aspect of bluegrass music that enchants fans, players and industry types from all camps.

"The best thing about bluegrass is the people that go to the shows," said Steve Robinson. "It's like a big family. You can't go to a rock show or a country show and get the same feeling. Once you go to a bluegrass show, it's a family."

Traditional vs. progressive

Just what is progressive bluegrass, anyway? If the band is doing a tune written by the Beatles, the Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan or (gasp!) the Rolling Stones, chances are very good it's a progressive band. If the pulse within the songs isn't fluid, but broken by the song structure into varied tempos, it's probably progressive. If the banjo ain't rolling, it may be progressive. If the vocals aren't high tenor for men or higher for women, it might be progressive. If you hear jazz voicings, you've got progressive bluegrass.

Any style of music has got to grow. One might think that progressive bluegrass is the inevitable direction for the music to follow and in some ways it is. And in some ways, it isn't.

"It walks a line," said Peter Kuykendall. "If it varies too much, than it loses what caught the fan in the first place. But in many ways, there are too many standards; they're too familiar."

"It's really almost gotten out of hand in terms of the styles of music," said Gary Brewer. "It's turned into so many different things. You got contemporary bluegrass, you got country 'grass, you've got newgrass. It's just gotten out of hand. So that's why it needs to stay in the traditional. Bluegrass music, especially in this region, is pretty much as strong as gospel. it's carried and stayed untouched and undefiled all through the years and that's something that we want to continue. That's why I feel like bluegrass music needs to stay more to the acoustic music because that's how it started. I'm not saymg that you have to sound like Flatt & Scruggs or Bill Monroe, because I write my own music. You can still do that and be in an original band. I'm living proof."

Bill Monroe is conciliatory toward progressive bluegrass musicians, yet protective of his legacy. He feels confident that some up-and-coming groups (like Brewer's) will preserve the music.

"Yes sir. I can't remember the names of a lot of them, but they're all over the whole country now," said Monroe. "They really want that fiddle in there, banjo and mandolin, play the guitar right, bass keepin' time in the music. They know that that will make it sound right. I don't want them to change it because it will hurt the music. There might be some new groups coming along that are changing bluegrass a little bit you know, but I try to keep mine the same way that I started it."

Concurs Ralph Stanley, "I just think that the traditional bluegrass is stuck more to the tune. It's just played different, you know. It's a more authentic sound. The new stuff reaches for rock and roll or country or whatever."

Once again, Dan Hays bridges both sides. "There's a lot of room for great discussions and great arguments," said Hays. "I think it's good and healthy. Any great art form will have these types of arguments. As long as folks are having that conversation, folks on both sides and on the middle of the spectrum will benefit from it. The day we don't have these discussions is the day that one of them is gone."

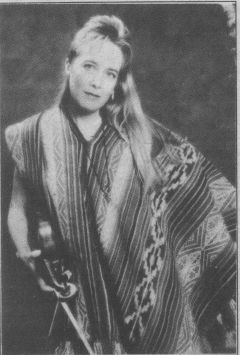

Alison Krauss: Bluegrass' biggest star?

Since she started winning fiddle contests in her early teens, Illinois native Alison Krauss has been big news in bluegrass. Now that her recent compilation album Now That I've Found You has hit Billboard magazine's Top 20 chart, Krauss is big news everywhere. The question isn't if she is bluegrass' biggest star, but if she is bluegrass. Most of the bluegrass world exults in her victory, but a few are melancholy. She's in the pages of Time magazine and on the airwaves of major country radio stations, but is she helping the bluegrass cause?

Krauss, in an interview printed in the June, I995, issue of Bluegrass Unlimited, shook off the responsibility some want to place on her and her Grammy-winning band, Union Station.

"We don't have any big hopes and dreams of taking bluegrass to another level," she told Bluegrass Unlimited. Krauss and Union Station are merely following their artistic muse rather than trying to make statements, stay within any boundaries or purposely cross them. Krauss readily admitted that all of her recordings aren't bluegrass.

"That song ("Baby, Now That I've Found You"), we're not pretending that's bluegrass by any means, you know?," she was quoted as saying. "I'd never say that's a bluegrass tune. I think we definitely do bluegrass and then we do stuff that isn't and I'd never put it under the same label.

I think that's where a lot of people get real mad, is that they say that something is being labeled bluegrass that isn't ... The bluegrass community has largely taken pride in Krauss' accomplishments.

"I think it's great that Alison has really made it," Doyle Lawson said. "We're proud of her. It's good for us and she represents the music well." Krauss has the enthusiastic approval of bluegrass fan non pareil Steve Robinson (an admitted traditionalist) and the Father of Bluegrass himself.

"I think that she's doing fine," Bill Monroe said. "She's got some really good music and they really sing good. She seems like a fine lady too."

Gary Brewer was not afraid to say what some purists feel, however. He freely speculated on Krauss' future, but was emphatic in pointing out that he was merely stating his personal opinion.

"My personal views are just mine, but I feel like she's helping the acoustic industry," Brewer said. "That doesn't necessarily mean bluegrass. I feel like she's getting in a position where she sure could help bluegrass, if she would. She could help by having bluegrass—actual bluegrass, not somebody who's changed over like her, but an up-and-coming real bluegrass act—open for her."

"Alison is doing her own thing, which is good," Brewer continued. "I feel like I'm happy for her and I feel like she's sort of straddling the fence between what I would just call an acoustic music group and country. I don't feel like she's totally country yet—no steel guitar, no drums, pianos or synthesizers – but the more she is drawn in that musical direction, the further away from bluegrass she'll get. Right now she's keeping enough bluegrass there where she can play a bluegrass festival. She's getting drawn in and most people will agree with that. And I believe the more popular she gets, the further away she'll get from bluegrass, maybe not her heart but her performance. And I believe in the long run, she'll be doing a whole lot more singing and a whole lot less fiddling, because that's what's selling her right now is her voice."

"I'm purely speculating on all of this."

IBMA chief Dan Hays has a different outlook.

"Alison Krauss is being Alison Krauss, in my opinion," said Hays. "She is trying to make the best music she can. I think that her music has a very, very strong bluegrass influence. I would characterize her music – if you look at her entire body of work and every concert she ever played — I would characterize her as bluegrass performer. Her latest single that has drawn a lot of attention to her is very much a country song, but that was something she did for another project.

"Has Alison helped bluegrass music? In more ways than you can count on both hands and both feet. I think she is contributing to bluegrass in more ways than can be fathomed right now. An emphatic yes."

"I'll simply say that every bluegrass festival that she has performed at in 1995, '94 and probably going back to 1992, she has been the biggest draw. Those fans also got to see Jim & Jesse, they also got to see the Nashville Bluegrass Band, they also got to see a regional or local bluegrass act that they never would have been exposed to. They will come back and not just for Alison. And they will not only buy Alison's album, but the album of another bluegrass act."

Peter Rowan's industry-wearied opinion was more neutral: "It's not the popularity of bluegrass on the charts, it's the musician. I'm tickled to see Alison up there."

Our attempts to interview Krauss were unsuccessful.

Peering into the future "I think bluegrass inusic will never die," said Bill Monroe. "it's here to stay.

There will be people that will come along if I were to quit and they would follow as close to me as they could so they would do it that way [traditional], take care of it and keep it that way. That's the way the fans and friends all over the whole world want it. They want the music played the same."

That's a sure bet. Traditionalists will always embrace a band that can accurately evoke the sound of the Blue Grass Boys and their early colleagues. Still, some folks get a scared, sad look in their faces when talk turns to the advancing age of Ralph Stanley and Bill Monroe.

They are the last two giants of the early years.

"When they pass, there's going to be a big, empty space," Peter Rowan said reverently. "But let's face it, the people who show up for Alison are not purists," he added, looking out over the crowd of a bluegrass festival headlined by Krauss.

The Bluegrass Hall of Fame in Owensboro, Ky. , has an interactive exhibit that plays a song then asks the visitor to vote on whether or not the song is bluegrass.

The votes are tallied and each song gets a percentage grade on its bluegrass content. The IBMA, which is involved in the museum, stays out of the fray regarding the definition of bluegrass music.

"From lBMA's perspective," said Dan Hays, "we do not adhere to a strict definition of what bluegrass is. As a trade organization that spans all kinds of styles and bands from across the world, we believe that it should be up to the musicians who make the music to decide what their music is."

Hays' personal opinion is no less slippery. "From a personal standpoint, I think there are ways to establish that something is bluegrass, but for every one of those criterion, there is an exception to the rule."

What is bluegrass? The definition of bluegrass is in the mind of each listener.

The writer of this article is indebted to Richard D. Smith's book Bluegrass: An Informal Guide (Chicago: a cappella books, I995) for its help in confirming the facts and dates of bluegrass music's history.