social bookmarking tools:

|

|

| Available RSS Feeds |

|---|

- Top Picks - Top Picks |

- Today's Music - Today's Music |

- Editor's Blog - Editor's Blog

|

- Articles - Articles

|

Add Louisville Music News' RSS Feed to Your Yahoo!

|

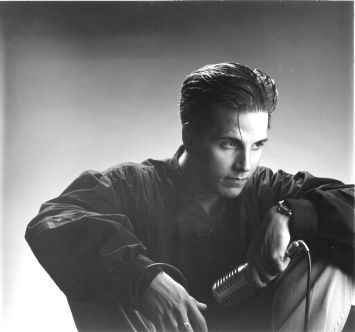

Shannon Lawson

By Allen Howie

It would be easy for an amateur psychiatrist to diagnose 26-year-old Shannon Lawson as schizophrenic. On the one hand, he'll wax enthusiastic about his bluegrass-based band, the Galoots, whose recently-released album Ham Days has been selling briskly at area record outlets like ear X-tacy. On the other hand, he warms up quickly to talk of his other project, the Shannon Lawson Blues Band, whose gig at Stevie Ray's the night before this interview kept him up until the wee hours. The dual identity can lead to some strange circumstances.

"The Galoots have actually opened for the Blues Band," he recalls. "So I've opened for myself before."

But the truth is that Lawson is no different from most ardent music fans, whose tastes often cross all sorts of boundaries in search of that elusive great record. He's just chosen two of the most narrowly-defined musical genres in which to ply his trade.

Like many artists, Lawson's appetite for musical adventure began at home – in his case, in Taylorsville, Kentucky. "All my dad's side of the family played music, so we all grew up listening and playing music when we were kids. My dad played guitar and sang, and as long as I can remember, he had a family band with his brothers. My uncle Glen played professionally for ten years when bluegrass was really big around here. But they all played locally. My brother and sister played. My grandfather played – his father played. It was just something we all did. I don't even know how far back it goes – but we're Irish, so it could have been brought over on the boat."

"Dad played guitar, fiddle, mandolin, bass, banjo. He played largely traditional music, but in college, he played rock. He played finger-style guitar, flat-picking guitar. He shattered his leg once, so he was laid up for a few months and studied classical guitar in bed. He was very inspiring as far as motivation."

Unlike many parents, Lawson's never discouraged him from pursuing music. Quite the opposite, in fact. "Dad bought me a guitar when I was seven. When I was a kid, four or five years old, they'd have these shows, and I'd get up onstage with 'em and pretend like I was playing. So I was used to the idea of being onstage – I was introduced to that real early.

"Anyway, he bought me the guitar, and he didn't have much patience, and I couldn't fit the bill. I learned a few chords, and that was about it. I think 'My Heroes Have Always Been Cowboys' was the first song I ever learned how to play. I remember practicing rhythm and trying to get the timing right."

Lawson's musical career might have ended there, except for that most elemental of persuasive forces – a taunting sister. "My older sister always sang and my older brother played and sang. My sister told me that I couldn't play guitar, and I felt very strongly that I could. It really bruised my ego, so I started picking it up again and getting serious about it. I guess I was thirteen or fourteen."

"Of course, I couldn't play very well – just strum a little bit. So I started delving into electric guitar, and all of the teenage stuff like Van Halen, Ozzy Osbourne, Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix. Frank Zappa. Anything I could listen to that seemed at all innovative."

Lawson's career took a step forward when he came to Louisville to attend college at the U of L. And like many things in his career so far, he was the beneficiary of a happy accident. "My first gig in Louisville was at the Granville Inn. That was the fall semester of school, in 1990. I was looking for direction, I was unhappy with school, and I decided I was going to make music a career. I had no leads, and no idea what I was going to do. I didn't know how to do it, didn't know how to promote myself, didn't have a band, didn't really know anyone around here.

"I just happened to luck into this job. I was at a friend's house playing, and this guy said he could get me a job. That's how I started playing at that bar. I got a gig for $30 a night and all the beer I could drink."

Apparently, that initial experience in the Louisville spotlight whetted his appetite for more, and classes fell by the wayside. "I stepped out of school," he delicately describes his exit from academia. And although much of his upbringing had been spent surrounded by traditional bluegrass and country music, his affair with the blues was about to begin.

"The old Cherokee Blues Club was open then, and I used to go in there all the time. Even though I wasn't old enough to get in, they used to sneak me in there. I met this guy named Top Hat, and he gave me a job playing guitar with him. That broke off into a reggae band (Dem Reggae Bon), so there were two working bands. I learned how to book and work and negotiate money – the business side of it – from this guy."

"Blues was a natural progression. I didn't make a conscious decision to go into blues – it just kinda happened. I listened to a lot of Hendrix, and his stuff is just flooded with a strong blues influence. I listened to a lot of Stevie Ray Vaughan, Buddy Guy, Leadbelly – and I was into lead guitar, too, so blues was just a natural thing. It was fun. Top Hat left town, and I kept playing with those guys, plus I started doing a little three-piece thing called the Barking Dogs that sprung from the Top Hat thing."

The Shannon Lawson Blues Band has a changing roster, with Lawson and Dennis Talley from the Galoots being joined by players like Howard and Geoff Gittli. "Howard plays trumpet and guitar, and Geoff plays saxophone and flute. They're very multi-talented. They sing back-up vocals. Geoff can also play drums and keyboards. And on sax, he's got that gritty rock sound. But we don't just play straight-up blues; we play a lot of soul and R&B, which is what I like more."

If you've never seen the band, you may wonder how the flute gets worked into a blues set. "We don't just play blues," Lawson points out, "so if we do something like Bill Wither's 'Use Me,' a flute solo is perfect for that. A lot of ballads work real well with the flute."

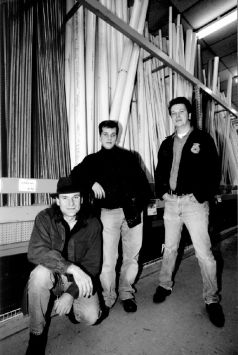

But if the Shannon Lawson Blues band had its roots in those early gigs at the Cherokee, the Galoots were the result of a chance meeting during an acoustic folk performance. "Everything in music has always fallen into my lap. I've been really lucky that way. At about the same time the blues band was getting together, I started the Galoots – me and Todd, Dennis and (drummer) John Hayes. We did really well in a town that was just full of blues, where the blues band was just another band."

"I was playing folk with Susie Woods, a local artist, at the Twice Told Coffeehouse," he recalls. "Her husband was a writer, and we met at a party. We talked and exchanged numbers and just ended up playing. I got to play on some recordings with her – it was a lot of fun. Anyway, (banjo player) Todd Osborne would come in with his girlfriend. I knew him vaguely from the past, and when we started talking, it turned out that he knew a lot of the same tunes that I did. We thought we'd just get together and play some of them.

So we got together and worked some up. Dennis had an upright bass he wasn't using, so we got him to drag that out. It clicked really well. We were very enthusiastic about it, and the crowds were really into it. Todd and I started playing all the tunes we knew, which were a lot of fiddle tunes and bluegrass stuff, so the song list grew really fast. At the beginning, I was doing more obscure Dylan tunes and a lot of weird stuff. But now we're writing more of our own material – it's more "Americana" style than bluegrass. It's got a strong country flavor, and some of them are bluegrass tunes, but it's developing from those things. I was raised on country music and southern rock, and I guess I really came back full circle with the Galoots. We thought we'd be confined to playing coffeehouses, but it expanded."

Lawson quickly found out that the life of a full-time musician involves a lot of decidedly non-musical chores. "I take care of the bookings myself, but I'm looking for a booking agent to take care of all that."

Lawson sometimes finds his love of performing at odds with his passion for writing and recording. "I'm very lucky to be able to play with who I play with," he admits. "Performances keep my playing sharp, but I sometimes find that when we perform too much, I approach burnout and I stop thinking about the music. It becomes automated. It's good to be able to go on auto pilot, to keep a consistent level to the shows, but for my personal satisfaction, it's horrible. I don't grow that way."

That's where his own material comes in. "Now, I'm in the best growing stage so far, approaching my own material, gathering ideas and formulating a direction more than I ever have. I'm just writing material, and wherever it goes, it goes. A lot of it's four-tack stuff, and some of it's probably going to be solo stuff."

Lawson credits Osborne with contributing greatly to the Galoots album, "Ham Days." " Todd and I have a really good writing relationship. He'll write out a good lyric, and he's good at formulating the idea of the song. So he'll bring the lyrics in, and we'll work on the melody together. I'll come up with something and sing it to him, and ask if it's what he would hear with it. He's really easy to work with in that way – he'll say, yeah, that's dead on.

Some of Osborne's song ideas are mere sketches, according to Lawson, while others have more substance. "On some things, he'll already have an idea melody. Like on 'Katie Walton,' one of the best tunes from the album, he pretty much had the melody down. All I did was fine-tune. I added the harmony structure and some changes on the lyric. It just fell into place."

Once work began on "Ham Days," it went quickly, remembers Lawson. "We started recording in mid-October, and we had the finished product in our hands just before Christmas. It was really quick."

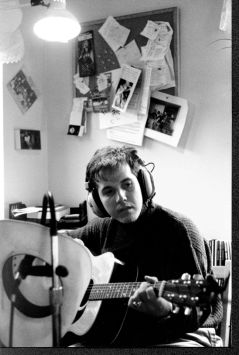

Part of that efficiency may have been due to where the music was made. "I recorded it in my living room on a four-track," Lawson says. "Before we started, the only songs we had written were 'Old Time Way,' 'Bardstown Road' and one other. Everything else was written for the recording."

That writing effort took the Galoots out of Lawson's living room and down into the country. "We went out to this place in Bullitt County that used to be a nudist colony. It's a big KOA-type place, with a big pond and a boat and all these A-frame cabins. We went out there and stayed overnight, cooked up some food. I went out in the rowboat and wrote a tune. We all went different directions to write – it was a great learning experience for me. I brought the four-track to the cabin, but only one track on the record was actually recorded at the cabin: 'Who's Dance Instrumental,' the prelude to 'Who's Gonna Have This Dance'. Everything else was recorded in my living room."

Lawson has some definite feelings about the pros and cons of studio recording. "My living room is so much more comfortable than the studio. You're not looking at the clock all the time. You can take a break, sit on the couch, think about what you're gonna do with this song, and play with it, because tape's not very expensive. We can just let it run and jam on things – let them develop naturally rather than having to hammer it out and know exactly what you're gonna do."

And Lawson is quick to admit that the studio experience stands or falls depending upon who you work with. "If you have a really good engineer and producer," he asserts, "they can make a world of difference. Every experience I had with a producer was a negative experience until I worked with a guy named Todd Smith (Union Tree member and engineer for Allen Martin Productions). He's a fantastic engineer. I did a song for "Harvest Showcase," and he engineered it. He just made the whole experience really easy."

So what was it about Smith's approach that impressed Lawson? "A lot of it has to do with attitude. I'm a vibe person – I pick up people's vibes in a situation like that. I'm kind of on the spot, because I'm the guy who's recording. I'm the one who's gonna make them stay there long or let 'em get out of there real quick, depending upon how easy I am to work with. So how they receive me sends back a vibe."

"But with Todd, he was totally 'What do you think? What do you want to do? Okay, I can do that.' He was totally relaxed, which relaxes me. He proposes ideas instead of just, 'I think we ought to do it this way.' And he cares about the finished product rather than just hammering something out to get the artist out of the building. It was a very natural process, and things just evolved. Super nice guy, and a great musician. He put a Hammond B-3 track on the song I put on Harvest Showcase this year, and it topped it off just like a cherry on top. It was perfect."

"He knows where to bring things in. He's good at layering the instruments so they sound like they fit together really well. Going into the studio with somebody like that would be great." But don't expect Lawson to settle into the studio anytime soon. "I really like to be able to take my time, relax and let things evolve. I've spent years recording at home – I've got hundreds of hours of me on the four-track by myself, where I play all the instruments and record all these crazy songs. There's a hidden track on the Galoots album. It doesn't have a name, but we'll call it 'I Can See You, Baby.' That was one of the songs – it was just a spontaneous thing. I never had an outlet for it."

Nor is that bonus track the only hidden treasure in Lawson's closet. Most, though, are more song fragments than songs, musical ideas for which he hopes to find a home. "I've got hours and hours. Like I'll have one lick on the guitar that intrigues me, so I'll record that, then build around it. It might not be more than 30 seconds long, but maybe a year later I'll use it in another song." Asked how he catalogues all this material, Lawson laughs. "It's not organized at all. I wish it was. I'd like to have it on DAT."

Getting his ideas down on tape is an old habit. "I think I started recording that way in high school. I rented a 4-track from Doo-Wop, and me and this buddy of mine, Jeff Shufeldt, used to write together. He's a great poet, now, a great writer. He inspired me a lot. We'd work together on these silly projects. He's the guy in the background laughing on this track. We were in the basement, having a few beers, makin' up stuff, just having a good time. We've been doing that for almost ten years."

Can fans of the Shannon Lawson Blues Band expect a record anytime soon?

"We're working on it," says Lawson. "I've got a stockpile of material for it. I just haven't deduced exactly how I'm going to record it yet – studio vs. home. The problem I have with home is that it's going to require a lot more work than the Galoots. The Galoots (sessions) were easy. I just put a mic on the instrument, a mic on the vocal, and that's it. But when you're doing the Blues Band, you have a lot of levels. Drums are a nightmare to mic – that's gonna be hard to do, just because I'm not a studio head. I don't know enough about studio stuff. I'm a novice at best. I know how to work a four-track, but that's as far as my studio expertise goes."

"My approach with the Blues Band," he speculates, "will probably be a live project. I tried to do a demo. We laid down the bass and drums, basic guitar and a scratch vocal, which I would later go in and redo. But there was no energy in it – it was dead, had no life at all. I hated it. So my next approach is going to be a live recording, definitely. It's hard to engineer, though – for me it is, anyway, 'cause I'm not an engineer. So I'm going to have to bring some help in, somehow.

"I think with blues or R&B, it's a little harder to keep the energy going in the studio (than with folk or bluegrass). You have the drums bleeding over into the other instrument mics, so if you make a mistake, you have to do the whole thing over. I think that's cool – I mean,. that's the way Elvis did it – but you can get really detached from something that way. It can be like putting pieces together – and you might have all the right ingredients, but it doesn't sound fresh – it doesn't capture that energy."

"Your main objective in the studio is not just to put out a body of music – I think it's to put out an energy. You want to produce a CD that, when people play it, they want to hear it over and over – something that's infectious. That's my main thing right now. I get obsessed with certain things from time to time, and right now, my obsession is to do original music and develop it and capture it, and mix the rawness and grittiness of being onstage with my own material. I don't really want to try the studio approach unless I have a good engineer. Money's a big factor, too, 'cause I have to finance everything myself. That takes awhile.

But in spite of his confessed technical limitations, Lawson remains pleased with things. "So far, I've still managed to do well. I'm happy with the product – I'm proud of it. It's like my child, I guess."

Lawson hopes to build on his successes. "I have a dream of being like an Ani DeFranco, and have my own thing going. Of course, your payoff doesn't work out unless you're really lucky. Forbes had the top forty entertainers, and they had a little blurb in there about DeFranco, whose investment is, like, $70,000, and her return is $75,000. So even though she's making more per record because she does it all herself, and does all the groundwork, after the investment, her return is a lot less. Yet she's in Time magazine, and everywhere else, so it's paying off for her. And I respect that. If I could do anything even resembling that, that'd be neat."

In a world where 20,000 albums get released in a single year, Lawson knows it's an uphill road. "Somebody pointed out to me," he says, "that in the 1950s, you could go around and play at a radio station – do a live thing. A lot of it was self-promotion. But then big companies would buy out smaller stations and tie up things, so you couldn't promote yourself that way. You could play on the local circuit, and spend a whole lot of money to get a recording done. Now it's totally reversed, to where you can do it all yourself, and I think that's great."

Lawson also sees a ray of sunshine in the proliferation of adult alternative stations and others who are willing to give a local artist some airplay. "The New 92 (WFPK) is fantastic about playing local music. For a local musician, that's great – it keeps you going, helps you keep food on the table." And Lawson applauds the existence on public radio of live radio shows like "E-Town" and "Mountain Stage." "A live radio show is where it's at for me," he says enthusiastically. "WSM, the Grand Ole Opry, to me that's real radio."

If one thing agitates Lawson, it's being labeled. "I hate that stigma of being 'just' a blues band," he says, since his Blues Band steps outside categories as often as not.

"Blues has been done to death, and is almost such a cliché anymore – not that I want to disassociate myself from it – but I want to expand into other areas. I've been fighting to change the name of the band (to take 'blues' out of it) for eons. I'm just gonna drop the blues part some day – it's got to go. I've been trying to get everybody to change that. It puts us in a box. I've had people come up to me on break right after we've done a real hot set, and they'll say, hey, why don't you play some blues? Then they'll leave mad. But you can't please everybody, and I don't really care to, anyway."

Bluegrass fans, he maintains, are even more intense than blues fans when it comes to staying inside boundaries. "The bluegrass fans are staunch traditionalists, for the most part, and they're extremely divided between the "newgrass" kind of thing and old Ralph Stanley tunes. It's a very hard crowd to please. I played with a band out of Middleton, Ohio, a bluegrass band called Union Spring for a little bit. We did a few shows up north – Maryland or someplace like that – and even out there, the crowd was very, very dry. At least the blues crowd will get into it. And they'll tend to follow you.

Just as Lawson sees his Blues Band as much more, he also dislikes having the Galoots pegged as a bluegrass group. "The Galoots have that bluegrass influence," he acknowledges, "but if I had to put a definition on it, I'd call it 'Americana,' because it's derived from things like country and bluegrass and folk and acoustic rock and blues."

Lawson points out an example of a successful artist who ignores those musical boundaries. "If I had a choice of a direction," he offers, "I'd pick something that would take the way Lyle Lovett has gone. And maybe I'm wrong – I don't know him or how he feels about his stuff – but I would think that he would be happy artistically with what he's doing. He's got a good base of success, yet he's not a super mega-star like Garth Brooks. I think that's the perfect area to be in. His crowd is dedicated and attentive. It's quiet, there's not a lot of screaming – it's a listening crowd. Ultimately, I think that's what every musician wants – for people to take them seriously."

So how does Lawson deal with every musician's nightmare – the person who talks right through the performance? "If I'm playing something with the Galoots – a low-key ballad – and someone's talking too loud, I'll bring the song way down. Then the people who are listening turn around and look at the people who are talking. Then they realize what they're doing, and they'll stop, and I can bring the song back up. That's a trick I developed at Twice Told. If someone starts talking to themselves in that place, it's loud. It works amazingly well. It's funny – people are self-conscious to a certain degree, so it works on that. They don't want to be the center of attention."

"That's one thing I like about Stevie Ray's – it's pretty much a show-oriented place. There are tables where people sit and watch the band, or they can dance, and then the bar is back out of the way. So it makes you feel like people are there to see the show."

Does all this mean that someday, Lawson will meld all of his influences into a single group? "The Galoots and the Blues band did all get together once," he recalls, "at a gig down at the Land Between the Lakes. It was a one-time thing, and it was a gas. We were playing down at this cabin, it got kind of loud, and all of a sudden we hear a shotgun blast. This guy up on the ridge got mad 'cause we were down there making all that noise, at this private party. But it was a lot of fun."

"In five years, I could see one band, one unit, as far as touring and such. I don't know what that would necessarily be. But I'd hope we have label support. But overall, I really just throw the cards up in the air and hope something will fall into my lap – with a gentle nudge of my own."

Whatever happens, expect Lawson to be as visible as ever, both in the spotlight and in front of the tape deck. "I don't really enjoy one thing more than the other, as far as recording vs. playing live. I really enjoy having a cassette of where we captured a moment on tape. Like we wrote a song, put something out and really like it, to where we want people to hear it. But I also enjoy performing." Press him on the issue, though, and he admits to a real fondness for recording. "I've had a lot of the performing side, and not as much of the recording side, and the distribution part. I really want to put out a lot of recordings, one right after the other. All of the profits from this CD are going to go back into more recording and promotion of the bands.

"I was really nervous about Ham Days," he admits, "because it was my first project, and I'd never had anything out, especially anything all original. It met my expectations – I'm really proud of it. I praise God that I can say that. I had this mix-down tape in my car, and just to make sure I was going to like it, I played it every time I got into my car. And I liked it more and more – and my favorite songs went from one to the next."

"That's been another good thing about the album – I haven't had any consistent good song / bad song report yet. I haven't had everybody say that one song sucks and one is good. Everybody likes a different song on the album. That's a good sign – it makes me very happy. We touched on a lot of bases. It's why I'm in it – it makes me happier than just about anything."